I keep thinking, if I wait a bit longer, Sean Drabbit will post a follow-up Facebook status saying “Sorry for the distasteful joke, Terry is alive and well. Ha, Ha. We gotcha!” But then I remind myself we aren’t kids any more, we know the pain of death all too well, and our days of childish trickery are behind us. Terry is gone.

Far too often in recent memory I have learned of the passing of dear friends through Facebook. It’s the new “norm,” but I hate it. I find myself in shock, staring at my phone’s screen — angered, saddened, numbed, detached, not knowing how to respond. After quietly brooding for most of the day, I finally have a moment to sit down and share some thoughts and memories of Terry and the substantial impact he had upon my life.

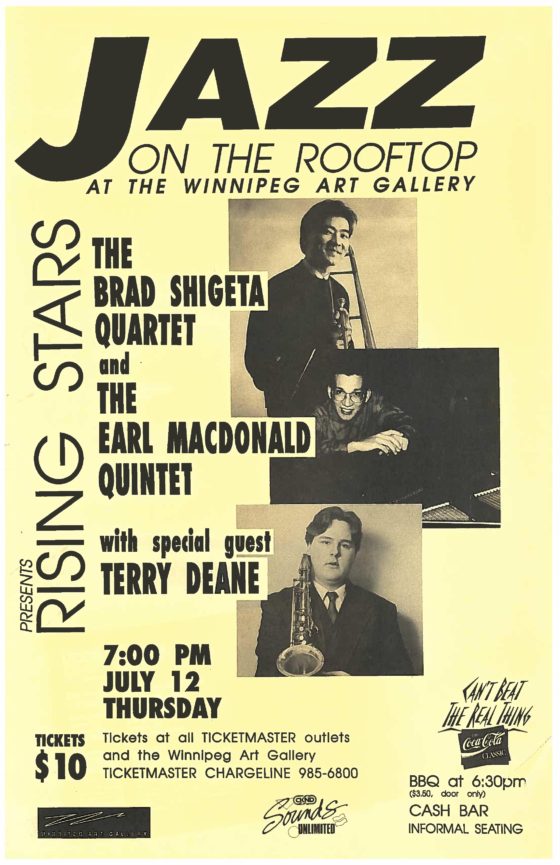

I have trouble remembering my first meeting with Terry, and if it was through our mutual friend, Dylan van der Schyff, or through a concert promoter who put us on a program together. In my archives I found the following concert poster from the early 1990s.

I think this concert happened before Terry, Sean Drabbit and Dylan van der Schyff moved to Winnipeg for a summer to play a 3 night/week jazz gig with me in the courtyard of Basil’s restaurant in Osborne Village.

What wonderful memories I have of that summer. I was probably 20-years-old and on summer break from studying at McGill. To pay for school, I had two summer jobs, in addition to working gigs at night. In May and June I worked in a greenhouse, doing physical labor (like shoveling bags of gravel and planting trees) and then in July and August I worked as a city employee with Parks and Recreation, running summer kids programs. I’d always set my alarm clock for 5:30 am so I could get in a few hours of solid piano practicing before riding my bike to work.

I remember Terry, Sean and Dylan living a very different summer experience. They rented a cheap apartment together in the worst part of Winnipeg, on Sherbrooke Street. They hung out, practiced and read during the day, and lived off our meager weekend gig money. In my eyes (or perhaps imagination) it was a glorious existence, and very far from my tiring reality. All three of them were highly focused on advancing their musicianship (and not raising money to go to school).

On weekends, we gigged, and when we weren’t gigging, we hung out, and listened to jazz. What struck me about Terry was his focused intensity. At that time, John Coltrane was his center of attention — specifically the period during the late 1950s when he recorded for the Prestige recording label. Terry was learning all of Trane’s solos from these albums. When we were together, most conversations involved Coltrane in some way. He was hyper-focused.

Even with my mother, Terry talked about John Coltrane. I remember one Sunday dinner at my parent’s house where my mom patiently engaged in a detailed conversation about how Coltrane’s sound could be attributed to his unique choice of reed and mouthpiece. Trust me… she had no interest in John Coltrane — although I joke that she could win a Downbeat Magazine Blindfold Test, because she complained only when I put Coltrane or Wayne Shorter records on the turntable.

I remember Terry as being an imposing saxophonist during this period. I have some recordings, which I’ll try to dig up from the archives and make public. Aside from Seamus Blake, who he admired, I wasn’t aware of many saxophonists in his age bracket who played with the level of mastery he achieved.

It surprised me several years later when I learned he had “set the saxophone down” and that he was golfing professionally. From there, he went on to become a saxophone repairman in New York City, and was in fact the repairman of choice for Kenny Garrett, Joel Frahm, Joshua Redman and many other respected players. Later he returned to Vancouver and opened his own pizza restaurant. I heard, and have no doubt believing it was the best pizza in the world.

Terry was an enigma to me — a true mystery. A guy with no formal education past high school, who held the secret to mastery, across classifications. He literally excelled to the point of mastery, in whatever he fixated his mind upon.

Isn’t this the exact opposite of what we are taught to do in school? The goal of school seems to be achieving balance — a bit of math, English, music, social studies, science, geography and… voila! We become well-rounded, well-equipped members of society. The problem is, we all become mediocre.

“Mediocre, ordinary, average, middling, middle-of-the-road, uninspired, undistinguished, indifferent, unexceptional, unexciting, unremarkable, run-of-the-mill, pedestrian, prosaic, lackluster, forgettable, amateur, amateurish, informal, OK, so-so, ‘comme ci, comme ça’, plain-vanilla, fair-to-middling, no great shakes, not up to much, bush-league.”

Not Terry.

Terry had it figured out. Learn one thing at a time, and learn it well. THAT was his gift, and his gift to me. Through Terry, I learned how to become good at something.

But that’s not all. Terry exhibited more bravery than most of us in life. He followed his passions, but never got stuck doing the same thing if it no longer brought him joy. He gave himself the permission to move on to something else, and when he did so, he pursued that interest wholeheartedly.

When I last saw him he was interested in opera, and talked about it enthusiastically for the duration of the meal we shared.

I am thankful to have known and learned from Terry Deane. He was truly an extraordinary person. One of a kind, really. His life gave an added depth to Billy Strayhorn’s famous motto, “Ever up and onward.”