Where Are We? How Did We Get Here? And Where Are We Headed?

Why do most jazz history textbooks (not to mention the infamous Ken Burns jazz documentary) end around 1970 and/or give only fleeting mentions of truly contemporary jazz? Is thirty or forty years still too recent to comment reflectively? Has nothing of artistic significance happened during this period? Are we waiting for something momentous to happen? Has institutionalized jazz education failed to produce innovators, with new, creative ideas to serve the advancement of jazz’s artistic progression?

I recently reread Eric Nisenson’s highly controversial book, “Blue: The Murder of Jazz,” in which the author wrestles with the “current” state of the jazz art form. It was published almost 20 years ago, in January of 2000. His arguments are worth examination and consideration — by performers and teachers, but especially by current university music students, who might not be fully aware that the continuum of jazz’s evolution was unnaturally disrupted during the 1980s and 90s.

Nisensen raises some excellent questions which in turn, prompt many addition questions.

Must jazz continue to progress to remain viable?

That jazz was highly progressive from the 1920s to the late 1960s is obvious. It’s evolution is easy to demonstrate through audio recordings, using almost any singular instrument. On trumpet, for instance, one can easily see the following lineage:

(Buddy Bolden) ››› King Oliver ››› Louis Armstrong ››› Roy Eldridge ››› Dizzy Gillespie ››› Miles Davis ››› Lee Morgan ››› Clifford Brown ››› Freddie Hubbard ››› Woody Shaw.

But then we get to the 1980s and 90s and what happens?

We observed the emergence of “The Young Lion Movement” — a neo-conservative, reaction against the avant-garde and jazz-rock fusion, spearheaded by record labels. Their primary goal was to market more accessible jazz music in the style of the 1950s and 60s, played predominantly by talented, young, well-dressed African-American men.

Moving from progression and rebellion to recreation represented a radical shift in the jazz world.

What lead to this?

- Dexter Gordon’s homecoming in 1976: After 15 years of residing and performing in Europe, the expatriate jazzman returned to the US to performed a triumphant stint at the Village Vanguard. These performances led to subsequent recordings and extensive promotion from Columbia records. Just imagine the impact of Dexter’s swinging, acoustic, hard bop sound, transplanted (seemingly from nowhere) into an era accustomed to hearing cross-over, disco-infused, commercial styles!

- Wynton Marsalis’ emergence as a charismatic, eloquent, marketable trumpet player, adept in both classical and jazz. He played with Art Blakey at the time, perpetuating the hard bop style of the 1960s.

Wynton was very outspoken in articulating a very narrow definition of jazz, formulated by his ideological role models, Stanley Crouch and Albert Murray. They were adamant in their narrow definition of jazz, and the adherence to a rigid set of rules. For music to qualify as jazz, they asserted that…

Wynton was very outspoken in articulating a very narrow definition of jazz, formulated by his ideological role models, Stanley Crouch and Albert Murray. They were adamant in their narrow definition of jazz, and the adherence to a rigid set of rules. For music to qualify as jazz, they asserted that…

- swing is essential

- the music must be acoustic (minimally amplified and no electronic instruments)

- the blues is an intrinsic element of jazz

- jazz reflects and stems from the culture and life of African Americans

These definitions have not only permeated our subconscious thinking, they have even crept into our current jazz history text books (Mark Gridley’s Jazz Styles, for example), despite the fact that each point could easily be argued (and disproved) using recorded examples.

Nisensen also points out another significant shift: until this time, jazz music always had a direct correlation to the times in which it was created. Blues drenched hard-bop of the late 50s and 1960s, for instance, reflected an era where African-Americans fought for racial equality. During this time the “Black Power” slogan was adopted, Black pride was prevalent, many musicians adopted African names, the Black Panther movement emerged, etc.

Should jazz be a reflective expression of its times? What if it isn’t? Is it then less artistically valid? If contextually disconnected, are its practitioners thereby musical liars?

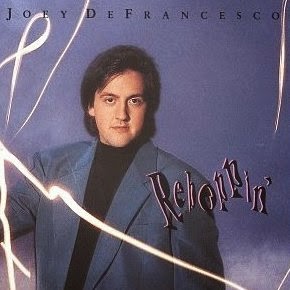

In the 80s and 90s, much of the music produced by young lions lacked context. A clear example is seen in Joey DeFrancesco, an Italian-American teenager from Philadelphia who was playing in the 1950s/60s hard bop style of Jimmy Smith. The music was swinging, bluesy and brilliantly executed, but was void of its original context and intent. Similarly, Brad Mehdau, an upper class optometrist’s kid from West Hartford, CT was playing in the style of Wynton Kelly. Obviously Brad has developed significantly as an artist since then, and has come into his own. But at the time, he was just another upcoming, half-done young lion, playing musical vocabulary from a previous era.

In the 80s and 90s, much of the music produced by young lions lacked context. A clear example is seen in Joey DeFrancesco, an Italian-American teenager from Philadelphia who was playing in the 1950s/60s hard bop style of Jimmy Smith. The music was swinging, bluesy and brilliantly executed, but was void of its original context and intent. Similarly, Brad Mehdau, an upper class optometrist’s kid from West Hartford, CT was playing in the style of Wynton Kelly. Obviously Brad has developed significantly as an artist since then, and has come into his own. But at the time, he was just another upcoming, half-done young lion, playing musical vocabulary from a previous era.

Even today, one can see that neo-conservatives uniformly revere and idolize their iconic musical forefathers. They work diligently to play, compose and even dress like Ellington, Monk, Coltrane, Davis, etc. Yet they reject the resolute intents of their forefathers to:

- play with their own unique sound/material,

- express themselves and the times in which they lived, and

- be committed to their own artistic vision.

Ongoing innovation was an essential part of the history of jazz. Is it necessary for the continued vitality of the art form?

Some people, including writer Tom Piazza, view Marsalis as the savior of jazz. Wynton brought about a resurgence in the popularity of the music, created a respectable performance venue for the genre at Jazz at Lincoln Center, improved the recorded quality of the string bass, and is an eloquent spokesperson for the music.

Nisensen on the other hand, argues that the dogma of the neoconservatives has:

b) obscured the music of forward-thinking, risk-taking musicians.

We shouldn’t forget that during the 80s and 90s there was a considerable amount of progressive music happening, beneath the radar of Downbeat magazine and the record labels who paid for advertising in such publications. We call these musicians “the lost generation”: Don Pullen, Richie Bierach, Dick Oatts, Fred Hersch, Hal Crook, Jim McNeely, Kenny Wheeler, Ed Neumeister, Billy Drewes, George Garzone, Billy Hart, Jerry Bergonzi, etc. Although artists of the highest caliber, who had paid their dues, none appeared on the front cover of magazines or had major label contracts.

The good news is that many of these forward-thinking artists turned to teaching, and have influenced subsequent generations. History has a way of correcting itself.

Why is it important to contextualize the young lion movement?

Today’s university students didn’t experience the young lion movement firsthand. They didn’t grow up reading and trying to make sense of Wynton Marsalis interviews. They must be made aware that the continuum of jazz’s evolution was unnaturally disrupted.

We must be mindful of philosophies that have entered our subconscious, through reading and listening to interviews by Marsalis and his disciples.

Building on tradition, rather than dwelling on it may be a healthier approach, if it is concluded that innovation/evolution is an important defining factor for this art form.

Questions with which all jazz musicians, teachers and students should grapple include:

- How strong a sense of tradition must we have?

- What aspects of the neo-classicist definition do you accept? Do you reject any aspects?

- How do you define jazz, and which of today’s musicians best exemplify it?

- What might your next album sound like? Do we need another quintet album in the style of 1957 hard bop?

Let me know your thoughts… and pick up a copy of Nisenson’s book at your nearest library.

Thanks Earl! Brings up several thoughts:

What of the current generation of innovators, whose “context” is a background in the jazz education system?

Anyone can be an innovator. It’s a very easy task to think of something that has never been done before. However, it is EXTREMELY difficult to do something new that is meaningful and of quality.

The lineage list of trumpet innovators you used as an example is a list of people who innovated WITHIN a tradition. I don’t hear many of today’s crop of experimentalists as any more evolutionary than Wynton. Avoiding tradition gets you no closer than aping it.

Your best point is with the “lost generation.” The fact that artists like these folks do not represent profits in the minds of the corporate sales/marketing/media complex has led to folks like Ken Burns being confused about the very history and evolution of the form.

The Neo-Conservative trend of the 80’s mirrored the Dixieland Revival of the 1940’s. In both cases, the instigators were critics and journalists, mostly those from New York City. Because our culture sees New York as the predictor of trends, and values New York media over local media, the things that get stirred-up in the New York press often infect the thinking of the society at large. When New York record producers find New York musicians and New York agents to cash in on these New York critics opinions, (and to cater to them) you’ve got yourself a movement

Hi Brad.

Thanks for weighing in. I don’t disagree with your comments. Perhaps “evolution” would have been a better word for me to use consistently throughout the article, rather than innovation. I did use it towards the end when I said: “Building on tradition, rather than dwelling on it may be a healthier approach, if it is concluded that innovation/evolution is an important defining factor for this art form.”

“Tradition” is also a loaded word. Here’s a direct quote from Nisenson, to which you will probably disagree: “The whole problem with this concept of jazz tradition is that the truth is, the only real tradition in jazz has been no tradition at all, or rather, the tradition of individual expression and constant change and growth.”

I can accept his point, because he includes “growth” at the end. I don’t think he’s talking about an ape sitting behind a piano keyboard banging, and someone calling it brilliant.

I’m curious about something you said in your 3rd paragraph. Do you view Wynton as fitting into the lineage I outlined? How is he evolutionary? I don’t hear it.

I’m also curious to whom you are referring in your opening question.

Thanks again for contributing to the discussion.

Two things come to mind. The jazz of 1957 (for example) had context in the culture (that was stated). The other thing is corporate America has worked very hard and spent a lot of money to manufacture music/lifestyle combos that they then could sell. Like the fertile ground of crops that have been distorted by Monsanto. Art does indeed reflect life.

I wasn’t referring to anyone, in particular, in my first paragraph, but I do see the current favorite groups that combine Pop, R & B and Jazz seem to be made up of musicians whose total Jazz experience is that they attended Jazz Studies programs. These are the groups lauded as innovators by my students when I ask them where they think the new music is coming from, or where it is going.

I do see Wynton fitting into the lineage, but my point is that he may have been so conscious of that role and responsibility that it may have prevented him from being more innovative. Being the torch bearer for a tradition is a heavy burden to shoulder

Here’s an excerpt from Wynton Marsalis’ Facebook post on June 12th, 2013, which presents an interesting counter perspective to my blog post:

I remember reading an interview Leonard Feather did with Monk that demonstrated this insatiable hunger for the next thing before the last thing had been tasted let alone digested. As the interview went on Mr. Feather arrived at and asked the inevitable question “What about something new?” And in classic Monk style he replied “Let somebody else create something new.”

All through the 1980s, I was hell-bent on trying to create new things and demonstrate them on recordings: a new modern collective horn improvisation with my brother Branford on “Hesitation”, new types of group interactions based on quick cues and open harmony on “Knozz Moe King”, contemporary ways to play traditional harmonies while playing in superimposed meters on “April in Paris”, playing all types of complex rhythms while keeping strict harmonic forms with Marcus Roberts and Jeff ‘Tain’ Watts on “Live at Blues Alley” and new ways of interpreting the sweep of the music from the New Orleans funeral to a 6/4 groove, with modulations before each solo, and a shifting improvised groove on each improvisation on “The Majesty of the Blues” with Herlin and Reginald Veal.

In the 1990s I focused on creating a new way of developing long-form composition for small group, utilizing short themes and a variety of emotions related to rhythmic setting on “Blue Interlude”, a whole new concept of form and motivic development across three long movements on “Citi-Movement”, a new concept of long-form related to the structure of a Mass with “In This House” and even a new way of interpreting the history, form and 10-piece orchestration on “Six Syncopated Movements”. In 1997, we performed “Blood on the Fields” and in 1999 put out 13 single CDs and a 7-CD box set of music of live music from the Village Vanguard. Into the 2000s we released “All Rise” that showcased new ways to bring a symphonic orchestra and jazz band together. We presented it to enthusiastic audiences all over the world and sold about 57 CDs to family and friends.

I won’t tell you about all the new music and arrangements that come out of the orchestra now from Ted and Victor’s recent commissions, to Sherman’s “Inferno” and Chris’ “God’s Trombones”, to everything Vincent Gardner touches, and on and on throughout the orchestra.

Over the years and through all that music, Still…..”Can you play something really, really loud and energetic, like with real electricity and a lot of anger?” “Can you play without all of those horns?”

“Can you play something new, I mean new, new, new?”

This past weekend the JLCO played a concert that showcased a small sampling of Ellington’s most avant garde compositions. Just before Saturday night’s concert, Chris Christian, a very intelligent and engaged 26-year old asked me, “What is the next new thing in Jazz?” Before answering, I reflected on the fact that very few people had ever heard any of this great Ellington music we were about to play, and that even though it was about 60 years old, it was still as fresh and modern as tomorrow. I replied, “The next new thing will be that people will listen to it.”

– Wynton