Not many bandleaders have the luxury of rehearsal time to experiment with orchestration possibilities. I do. My students at the University of Connecticut played a large role in refining this music prior to recording it. We spent a semester, not only rehearsing and preparing the music for performances, but also engaging in activities like examining multiple versions of short passages, orchestrated in different ways, to determine which one was most effective.

It was a win-win situation. I benefited by getting a better musical result in the end and saving precious rehearsal time with professionals, while my students experienced the creative process unfolding, as they worked directly with the composer whose music they were preparing. Plus, they delighted in pointing out imperfections found within their parts — whether it be an enharmonic spelling, an awkward page turn, or a musical figure which lay uncomfortably on their instrument.

About a month prior to the recording, tweaked, revised versions of the music were sent to the selected professional musicians. Being able to send electronic PDF attachments is a lot simpler and less expensive than sending packages through the mail, as we used to.

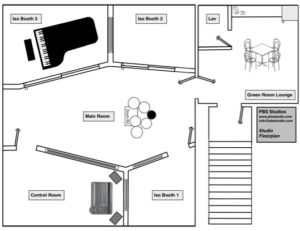

Peter Kontrimas’ recording studio (PBS) in Westwood, Massachusetts was selected for the recording. I have hired Peter for my last five recordings projects and have the utmost confidence in his work. His Yamaha grand piano is excellent, plus his little studio is perfectly configured for an ensemble of this size. The piano, bass and drums could each be isolated from the horns, which were seated in a semi-circle, in the main room. Peter’s control booth and kitchen also had the potential to serve as isolation booths for soloists.

Because some of the musicians would be traveling from as far away as New York City, it made sense to record the album in one, long session. Knowing that meal breaks were essential, but could take a lot of time, and disrupt the session’s momentum, my wife and I prepared and packed lunch for the band in a large cooler. There were cold cuts, fruit salads, egg salad, etc. and drinks. Dinner would be eaten out, at a nearby Chinese restaurant, to allow a regrouping break after hours of concentrating.

Because some of the musicians would be traveling from as far away as New York City, it made sense to record the album in one, long session. Knowing that meal breaks were essential, but could take a lot of time, and disrupt the session’s momentum, my wife and I prepared and packed lunch for the band in a large cooler. There were cold cuts, fruit salads, egg salad, etc. and drinks. Dinner would be eaten out, at a nearby Chinese restaurant, to allow a regrouping break after hours of concentrating.

Although the seating configuration was determined, and most microphones were set up ahead of time, it always takes a little while to get everything in place, tested and ready to go before ‘hitting the record button.’ The rhythm section arrived first and tested their levels, followed by the horns. In about an hour and a half, we were all set, complete with headphone mixes to everyone’s satisfaction.

Although the seating configuration was determined, and most microphones were set up ahead of time, it always takes a little while to get everything in place, tested and ready to go before ‘hitting the record button.’ The rhythm section arrived first and tested their levels, followed by the horns. In about an hour and a half, we were all set, complete with headphone mixes to everyone’s satisfaction.

Each piece was typically recorded three times, from top to bottom. With Ben Bilello on drums and Henry Lugo on string bass, the time rarely fluctuated, which would prove to be helpful later, in the editing process. To keep the tempos identical from take to take, we often used my recorded “count off” from the original take (with me saying “one, two… one, two, three, four”).

If a portion of the tune was poorly executed, we might pause and rehearse it and then re-record just that passage, to insert later, when editing. Also, in songs that included fermatas and clean breaks between sections, we used this to our benefit, only recording that part, before moving on.

If a portion of the tune was poorly executed, we might pause and rehearse it and then re-record just that passage, to insert later, when editing. Also, in songs that included fermatas and clean breaks between sections, we used this to our benefit, only recording that part, before moving on.

Instrumental solos were typically recorded live, and in the isolation booth, whenever possible. During breaks between tunes, some of the soloists took “second stabs” at their solos, overdubbing alternate versions, from which we could choose later.

Both trumpeter Jeff Holmes and I took notes throughout the day, cataloging which ensemble “takes” and solos were best, and what glitches might need to be addressed in editing. I also encouraged the musicians to write messages to me on their music, for later reference. They would circle passages where mistakes were made, and indicated on what takes they were played inaccurately/correctly. Referring to all of these lists made my subsequent work easier.

In all, the recording session on 11/29/2015 took thirteen hours. Overall the day was enjoyable and highly productive, but of course there were a few tension-filled moments. Everyone was highly focused and took care of business.

Following the recording, I spent a few weeks listening to Peter Kontrimas’ rough mixes, deciding what takes were best, and then writing notes with regards to what “fixes” needed to be made. I then transferred the information in my lists to my scores with a red felt-tipped marker.

In all, I probably spent a dozen, six-hour days, spread over several months, editing and mixing at Peter’s studio. We started with large-scale edits, like combining takes, and eventually worked our way down lists to address minutia, like fixing note durations and releases. At times it was tedious work, but the music benefited, and now reflects how it was envisioned.

In all, I probably spent a dozen, six-hour days, spread over several months, editing and mixing at Peter’s studio. We started with large-scale edits, like combining takes, and eventually worked our way down lists to address minutia, like fixing note durations and releases. At times it was tedious work, but the music benefited, and now reflects how it was envisioned.

Because of my university obligations and parenting duties, it probably took me longer than most to complete the post-production phase of this album. A little more than a year after recording it, I was ready to have it mastered. This was a one day process, where in addition to putting the songs in order, we made subtle tweaks, and ensured every song was equally loud, so listeners wouldn’t be adjusting their volume dials between tunes.